Some years ago I helped to compile an article on Anglo-Saxon food, for a DASmag. Since then, new research has been done on the subject of the diet of Dark Age Man, and Ann Hagen has recently published A Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Food – Processing and consumption. In truth, little more is revealed on the shopping list of Dark Age eating but it does bring many other associated topics under its cover, such as feasting, fasting and dietary deficiency.

The book has been split into two sections under the headings of Processing and consumption, finishing with a conclusion and appendices. This is not a cook’s book. There are a few recipes and I thought rather ‘woolly’ information concerning food items and cooking methods often derived from Medieval sources. One of the most tantilising items is surely the description of the preperation to make a sage omelette, taken from an Anglo-Saxon leechdom (medical document). If only she had added a few further dishes. On the other hand, the section on pickling seems to be pure supposition. The achievement of this book is to bring a lot of material under one cover, with innumerable references to the source material for those keen enough to follow them up.

As an alternative source of information, I decided to take a look at Old English riddles. Here food items can be identified, although the solutions are hinted at through innuendo: a wineskin, red wine, onion, mead, barley, a bullock, a cock/hem, dough, a butter-churn, oysters and garlic. A good meal could certainly be arranged from these items. Some other manuscripts also provide information of processing and end products. A translation from Soloman and Saturn II reads, “a chunk of food falls to the floor, is picked up, blessed and covered with pickle and eaten.” (I would suggest that the blessing was due to the morsel not falling buttered side down!) The word translated as ‘pickle’ is also sometimes translated as ‘seasoning’ but what was this pickle or seasoning? We don’t know and are unlikely to find out, unless an unopened jar is found.

Notes on bread

Bread was a staple part of the Dark Age diet – when it was available. There were household bakers, communal bakehouses and commercial bakers to ensure a constant supply. Loaves were used in payment of rent or wages and the old English words hlaefdige (lady) and hlaford (lord) are all derived from the word hlaf meaning raised loaf.

When it came to bread-making, there was a marked preference for the lighter textured white wheaten loaf, which was not available to all. Locality or poverty made it a rare commodity for some folk. In milder parts of the country, both spring and winter wheat could be sown; the latter was the more highly prized, (under the Romans, Britain was a major wheat producer). Other cereals grown were rye, barley and oats. Sometimes a mixed crop of wheat and rye was grown as a winter crop, to produce loaves of mixed grains with names such as monkes corn, masdeline and meslin (meslin means mixed, maybe half rye, half barley).

A lighter loaf was not easy to achieve with English wheat, which is low in gluten, and additions of other grains certainly didn’t improve the texture. Barley makes a flat, grey, dry loaf, so was used to make the flat barley bannocks in areas such as Wales, Northern England and Scotland, where wheat growing was difficult. Barley imparts a good flavour and is also the source of malt for beer.

Rye, when used in bread-making, makes a dense loaf which is well flavoured, however, its gluten content, although good, is not comparable to wheat. It could also be a little hazardous if infected with the ergot fungus, the raw material for LSD.

Oatmeal was the cereal that could be grown in the wetter and more northerly parts of Britain. Oaten breads are well flavoured, with a good fat content. They are nearly always flat griddle-baked bannocks or oatcakes and weigh heavily on the stomach.

Mixing any of the above cereals to taste or availability was frequently done and in times of shortages, beans, tares, lentils, acorn flour, hazel flour and alder flour, were also added to eke out a meagre supply.

All harvested cereals need to be stored, either on the stalk in stooks or as dried and flailed grains. In this state it could be stored for many months, if kept cool and dry. Once milled the flour could be stored for a limited time before going rancid; only about three weeks. This meant milling just enough flour for current needs only. It has been suggested to me, by a miller, that grain storage without temperature and humidity controlled conditions, would make supply viable for approximately six months, thus making bread a seasonal food, even in years of a good crop.

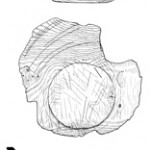

The Romans introduced water-powered mills and by the Doomsday survey, some six thousand were established in England. Otherwise, milling was done by pounding in a hollowed stone with a pestle, in a saddle quern, or by a hand powered mill. The prefered material for quern and handstones had to be imported, as it was the Neidermendig lava stone, fragments of which have been found on many Saxon sites and in Viking York. Poorer folk would have used locally available grinding stones. The fineness of the flour was dependant on the number of times it was sieved or bolted and it is probable that only the richer members of society would have regularly used fine grades of flour.

The question arises, did they use yeast? It seems likely from the available evidence, but there can be no certainty. The ‘dough riddle’ from the Exeter Book can be taken as evidence for yeast if we have guessed the correct solution. To quote the riddle, the dough “…thrusts, rustles, raises its hat.” But, not even modern yeast would give this effect! Yeast, if it was used, would most likely have been the by-product of brewing, or the sour-dough method could have been used (a piece of fermented dough was kept from the previous day’s baking and used to ferment the next batch).

Ann Hagen offers us the startling piece of information that loaves could be large or – yes you’ve guessed it – small. They could also be made into rolls as well as loaves. Methods of cooking bread ranged from baking on hot stones or on an iron griddle (perhaps for unleavened bread), under an inverted pot covered in embers, or baked in a clay oven for an ofen baocan hlaf (oven-baked loaf). A plain loaf may have been seasoned with seeds such as poopy, dill, caraway, fennel or sweet cicely. The dough could be enriched with butter, cream, milk, eggs; also sweetened with honey and fruits. Such a loaf would probably be reserved for high days and holidays.

Meat, Poultry and Fish

The domesticated animal remains that are most common on archaeological sites from our period are: cattle, horses, sheep, goats, pigs, poultry, cats, dogs and bees. These were augmented by fishing and by hunting of wild beasts and birds. It is possible that of all the domestic animals kept, pigs were the most numerous. Although fewer pigs’ bones have been found this would be the case if they were eaten as bacon; having been slaughtered, boned and salted elsewhere. Cattle and sheep (excluding cattle used as draught animals) were obviously kept for dairy products and meat. Young animals – lamb, veal and kid – were also eaten, as only enough animals to replace older beasts would be kept, the rest of the young were surplus; to be sold or consumed. Extra animals would require more fodder.

There is evidence for areas of the southwest of England to have specialised in the production of cattle; where the weather was mild and pastures were rich. Religious establishments also had an interest in cattle production – for velum from the calves’ skins. Animals would have been slaughtered by their owners or by a professional butcher. By the end of the tenth century oxen had to be slaughtered in the presence of two witnesses, probably to suppress cattle theft. The meat would have been consumed locally, either cooked or preserved. An excess may have been sold in butchers shops, which were in use by the end of the period (flaesc straet and flaescmangere). Meat was hung and jointed, the brain and tongue were extracted from all meat animals and bones were split to obtain the marrow. It seems that hooves and lower legs were considered as waste.The use of offal has not been found in manuscripts and leaves no archaeological evidence.

Other animals eaten included wild boar, red deer, hare, beaver and bear (the last two were becoming scarce but as yet there was no restriction on who could hunt). Regarding horse-meat, Christian Anglo-Saxons did not eat it as it was considered a food of pagans. But, we know that the Vikings did eat horses, even if it was their transport!

Poultry was kept for eggs and meat: chicken, ducks (mallards) and geese (grey lag). Other birds found were: common crane, golden plover, grey plover, black grouse, wood pigeon and lapwing. These were the wild birds caught locally to add a bit of variety to the diet.

Lastly, fish and shellfish. Many remains have been recovered from Jorvik (Eoforwic in Anglian) oysters in substantial numbers, cockles, mussels and winkles (in smaller amounts). Saltwater fish: cod, herring, haddock, flatfish, ling and horse mackerel. Freshwater fish: pike, roach, rudd, bream and perch. Along with smelt, eels and salmon. Archaeologically, no fish nets or traps have been found but iron fish-hooks with long lines have been recovered. However, from the coastal site of Hamtonwic, in decline by the 840s, little seafood has been found. The food remains were beef, mutton and pork. This may indicate national preferences (Saxons didn’t like fish?).

Dairy Products

Fresh dairy products were a seasonal bounty and could be preserved in the forms of cheese and butter; in winter fresh milk would be very scarce. The milk obtained from cows, ewes and goats was used to make cream (fletan), possibly clotted cream, butter (buteran) and cheese (cese). The by-products, buttermilk and whey were either drunk or processed again into cheese and butter respectively. Butter was salted or unsalted, as was cheese. In both cases the salt was used as a preservative. About twenty to thirty pints of milk are needed to make one pound of butter.

Whole milk was a luxury drink, more often it was drunk semi-skimmed. Ascetics tended to drink milk rather than intoxicating beverages, often adding water. Using milk the following delights could have been made:: syllabubs (comprising fresh milk or cream and wine or cider or ale, made into a frothy liquid, sweetened and flavoured), sweet curds or junkets (a type of milk pudding of milk and rennet, sweetened and flavoured), frumenty (a kind of porridge, spiced, sweetened and enriched with cream or egg yolks). The above are traditional English dishes and evidence of their early consumption cannot be verified.

Dairy work was, like bread-making, woman’s work; the churning, the making of butter and cheese, then the selling of the produce in the towns. According to various leechdoms, butter was far better than milk for ‘boiling’ herbs in and for cooking vegetables.

Cheese could be soft or hard. Rennet was available for the coagulation process, though plants could also be used, such as the flowers of wild thistle, safflower seeds and lady’s bedstraw. Some cheeses were eaten fresh and others were stored salted, these were produced either on a domestic scale or they were made in quantity on a large estate, for consumption or for sale locally. Some cheese may have been smoked in storage but wherther this was incidental or intended we cannot tell, as they could be

stored by hanging under the roof, to keep from vermin whilst maturing. Cheese (and occasionally butter) has been recorded as a food rent, like bread.

Vegetables

There seem to be few vegetable remains and even less written about them, the Viking dig at Yorkrevealed carrots, parsnips, celery and possibly brassicas (cabbage family). Another source adds cabbages, onions and leeks. Two Old English riddles give us onion and garlic as answers. Therefore I consulted a guide to edible wild plants, as many have a long tradition of being eaten and we can probably assume that this trend stretches back to the Dark Ages. Doubtless, during times of meagre stores any extra bulk that could be added to a meal supplied from field, garden or hedgerow, would have been used. To this end I have listed below plants that are either native or introduced by the Romans and all have a tradition of being eaten.

- Bargeman’s cabbage (brassicas campestris) – an introduction of unknown date. Cabbages have been collected for their roots, leaves and seeds used as a condiment. The plants were later selectively bred for their roots; the modern turnip. Brassica oleraceus – the ‘wild’ cabbage, was originally found on rocky coasts and would have been a cultivated crop inland. After several seasons of careful cultivation and seed selection, decent specimens of many wild plants can be obtained.

- Charlock (field mustard) – native. A cabbage-type plant that has been used as fodder, but has been cooked in milk in the Hebrides and Ireland in times of shortage.

- Sea kale – native. A shore plant that was a favoured vegetable of the Romans. It is rather scarce now, but still considered a local delicacy where it is available.

- Water cress – native. Well known for its medicinal properties.

- Garlic mustard – native. Leaves and shoots are eaten.

- Bladder campion – native. The young shoots are eaten.

- Chickweed – native. The leaves and stems are eaten.

- Hastate orache – native. Much prized by the ancient Greeks as a pot herb.

- Wood sorrel – native. A pot herb and can be used to curdle milk to make cheese.

- Broom – native. (Not Spanish broom which is very poisonous.) The young buds are eaten as a vegetable and they formed an essential ingredient in beer making before the introduction of hops (they give the bitter tang).

- Silverweed – native. Grown by the Anglo-Saxons as a root crop, known to have been continuously used in parts of northern Scotland as a reserve crop in time of shortage.

- Saladburnet – native. Used fresh and also as a fodder plant.

- Cow parsley (wild chervil) – native. Young shoots can be used.

- Sweet cicely – introduced by the Romans. All parts of the plant can be used. The seeds are widely used for flavouring.

- Earth nuts (pig nut) – native. Beloved by pigs! This plant has root tubers that are hazel nut sized.

- Fennel – probably introduced. Leaves, shoots, seeds and bulb can be used. The Emperor Charlemagne had this vegetable grown on his imperial farm.

- Wild Angelica – native. Shoots, stems and roots can be used.

- Wild Parsnip – native. Cultivated for its roots, although they would not be as large and succulent as modern parsnips; reasonable specimens could be obtained by cultivation and seed selection.

- Wild carrot – native. Like the wild parsnip, wild carrots in their natural state are rather poor food but after cultivation reasonable specimens can be grown.

- Stinging nettle – native. The young shoots can be used as a vegetable and have also been used to flavour beer.

- Water mint – native. Used as a pot herb.

- Lady’s bedstraw – native. Traditionally used in Cheshire cheese with rennet; it will curdle milk on its own.

- Wild thyme – native. Used as a pot herb.

- Wild marjoram – native. Used as a pot herb.

- Tansy – native. Used in tansy cakes and puddings in the Middle Ages.

- Chicory – native. Roots and leaves used.

- Dandelion – native. Roots and leaves can be used with discretion.

- Great Burdock – native. The young stems were once popular as a vegetable.

- Ramsons – native. A type of wild garlic, the leaves and bulbs can be used.

This is not an exhaustive list and I cannot say how these plants were prepared for eating, whether they were used fresh or cooked. Maybe some were only used medicinally and were not used generally as a vegetable at all. Until access is given to some of the more obscure manuscripts, this area of diet will remain open to speculation.

Herbs

Many plants used as pot herbs have been mentioned above. Herbs and spices known to have been used for flavouring were dill, coriander, mustard and cumin, although there is reason to believe many more were actually used than have been archaeologically found. Rose and elder flowers could also have been used for flavouring.

Fruit

The fruit remains recovered from the Viking were apples, sloes, various small plums, bilberries, blackberries and raspberries, which formed the bulk of the fruit intake. Hazelnuts and walnuts were also found. To this list could be added: wild strawberries, rosehips, pears, haws (hawthorn berries) and elder berries. Medlars, quinces and mulberries are all introductions of uncertain date. Medlars and quinces are both natives of Asia and the Mediterranean Area. The mulberry is from the Far East, but the actual origin is now obscure due to its ancient and extensive cultivation. As pointed out earlier, Ann Hagen in A Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Food is apt to write a very woolly passage and on the subject of deserts and cakes she doesn’t let us down. She does say that the Anglo-Saxons enjoyed various “dishes of milk/cream/curds, sometimes with wine, or with the addition of meat”, but beyond that the rest is just speculation, or drawing on some later Anglo-Norman evidence. No conclusions are drawn, but she does tell us what they could have made with the ingredients

available.

Drink

To help consume all this food, there were drinks: ale, cider, mead, other fruit based drinks and wine. It is likely from evidence found, but not conclusive, that wine was imported from Germany. It is as likely that it was brought in from Frnace as well. It is said that grapes were cultivated in some parts of England from Roman times, though this has to be substantiated. If these drinks were too rich, there was milk (drank with fish), whey, buttermilk and water.

Conclusion

To finish this essay I have taken the liberty of reproducing Ann Hagen’s conclusion, as she does a good job of broadly summing up the known facts, without speculation. “Anglo-Saxon cookery seems to have been based on boiling, a method practised particularly in subsistence economies, were all parts of the animal have to be utilised. The nobility may have been able to indulge a preference which is now widespread for tender joints which do not need stewing. Barley and other cereals, dried beans and legumes were commonly used in stews, brewits and soups.

“Some basic procedures were already established in Anglo-Saxon times: clarifying butter, whipping cream, salting vegetables and serving them with butter, or with oil and vinegar, for example, but one important difference is a quatitative one: numerous herbs were used to flavour Anglo-Saxon dishes. That the cuisine used the resources to hand imaginatively is emphasised by a comparison bewteen Anglo-Norman and early medieval French recipes. The Anglo-Norman recipes make a considerable use of fruit and flowers not found in any French recipes. They are also far more specific and discriminating in the spicing of different dishes. Features of the Anglo-Norman recipes which arguably represent the native English tradition are custard tarts with dried fruit, strawberries, blackberries and pears, hawthorn and rose flowers; white meat stews

with elderflowers, mulberries or pears; red meat stews with rose petals, hawthorn blossoms, cherries and stawberries. There seems to have been a predilection for sweet dishes as a number of the recipes include fruit or honey. There are desert dishes: hazelnuts used in flour and flour milk and elder flowers used to make a pottage, for example.

“As well as fruit sauces and seasonings, colourings and garnishes were seen as important as part of the overal visual effect…”

As a quick reference guide, here follows a categorised list of the foods and notes on cooking methods available at that time.

Vegetables

Carrots (though they used to be white), cabbage (of the loose spring green variety), sea kale, onions, mushrooms, parsnips, garlic, peas, runner beans, spinach, celery,

leeks, field beans, skirrets, Alexanders, Good King Henry and other leafy vegetables (anything green and non-poisonous).

Meat

Beef, pork, mutton and lamb, goat, red deer, venison, wild boar, hare, horse (vikings only).

Poultry

Chicken, geese, duck, plover, black grouse, wood pigeon, lapwing, wild fowl, seagulls – generally all wild birds!

Fish

- Freshwater: pike, roach, rudd, bream, perch.

- Saltwater fish: herring, cod, haddock, flat-fish, ling, horse mackerel.

- Estuarine fish: oysters, cockles, mussels, winkles.

- Also: smelt, eels, salmon.

Dairy

Butter, milk, cream, cheese (soft, hard and smoked), eggs (chickens, ducks and geese).

Herbs/spices

Horseradish, dill, coriander, hops, agrimony, thyme, mint, marjoram and rosemary. Spices were rare and very expensive but may well have been available to some degree!

Grains

Oats, wheat, rye, barley, chick-peas, pearl barley.

Nuts

Hazelnuts, beech-nuts, walnuts, chestnuts (not the sweet ones), almonds (expensive).

Fruits (fresh or dried)

Apples, pears, grapes, sloes, cherries, plums, blackberries, bilberries, raspberries, elderberries, wild strawberries, blackcurrants, redcurrants, quince, medlar, mulberry.

Beverages

Milk, ale, beer, mead, fruit wines, cider, buttermilk.

Cooking aids

Olive oil (expensive), lard, salt, honey.

Cooking methods

- Boiling: in a cauldron over the fire pit or in an animal skin with hot stones.

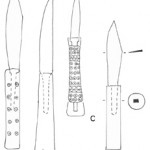

- Roasting: large rotary spit or small skewers, generally over an open fire.

- Grilling: spiral griddle, hanging griddle or on a ‘barbecue’.

- Baking: wrapped in leaves or clay and left in the embers or use an upturned kettle.

- Frying: in a frying pan or griddle.

Clay or turf ovens may be found in houses.

Baking in temporary encampments was done in a stone lined pit, a lidded cauldron or a flat stone next to the fire. Liquids that needed to be warmed were poured into a suspended animal skin, and then hot stones were dropped in.

Storage/preserving

Preserve meat and fish by salting, pickling (in brine or whey, whose lactic acid prevent food spoilage) drying or smoking (the smoky upper reaches of the longhouse helped to keep meat hung there from spoiling) Dried herring were eaten like biscuits, spread with butter.

Serving

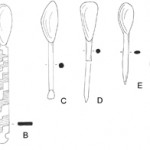

Two meals were eaten daily and wealthier families would have a linen tablecloth. Meats were served on wooden trenchers/plates and eaten with a knife, while stews, porridge and similar items were served in wooden bowls and eaten with wooden or horn spoons.

The Dark Age Dinner revisited by Ricula, DASmag Autumn 2000 and Grub’s Up by Freyja, DASmag Spring 2003.